Patti Callahan Henry has lyrically weaved tales of love and self-discovery for 12 New York Times bestselling novels now, setting each in distinctly Southern places from the Carolina Lowcountry to familiar landmarks near her Mountain Brook home. But her latest project took her on a new road, penning a novel of Joy Davidman, a poet, writer and the woman C. S. “Jack” Lewis called “my whole world.” Patti, here writing as Patti Callahan, traces Joy’s story from transatlantic letters from New York to London to Oxford, breathing her extensive research into her storytelling voice in Becoming Mrs. Lewis.

“For the first time in 13 books, I don’t feel like I am pushing myself because this is all about Joy,” she told us over lunch this summer. “You have to meet this amazing, fiery woman who has something to teach all of us about living a better life and being brave and making choices people don’t approve of.” We recommend reading the novel for yourself after it comes out Oct. 2, but first here’s what Patti had to say about how her world became entrenched in Joy’s.

How did you get interested in writing about Joy Davidman?

I am a preacher’s kid, so I grew up with C.S. Lewis’s books. I read the Screwtape Letters when I was too young to read them, and I fell through the wardrobe into Narnia. I had heard about his wife, Joy, through the years, and I am always fascinated by improbable love stories. But really it all started when I was at a Christmas party with about 10 of my writer friends in Nashville, and I was talking to my dear friend Ariel Lawhon, who writes historical fiction. We were talking about how I have read more historical fiction than anything else, and how I have thought about writing it but that it’s such a departure from what I do. She asked who I would write about if I could. I don’t where it came from, but I said, “I would write about C.S. Lewis’s wife. She is so fascinating!” She got this look on her face and said, “If you don’t do, I am doing it.” And I started it the next day.

How did you want to frame the story?

How did you want to frame the story?

The question I started with is: “How in the world did they ever get together?” It’s impossible. Joy is this Bronx-born woman 16 years Jack’s junior who is married with two kids living on a farm in New York, part of the New York literati, a communist, an atheist who had a conversion experience. Jack’s brother Warren wrote in his journal, “We received a letter from this fascinating American woman.” So whatever she wrote grabbed their attention.

I wanted to know her journey. I loved the movie Shadowlands, but that’s the story of her dying. I wanted to write a book about her living. There wasn’t a single voice telling her to do what she did. How was she brave enough to save her own life? That was the whole seed of the story. I found this quote she wrote in an essay called “On Fear”: “If we should ever grow brave, what on earth would become of us?” I think she asked herself that and answered it with her life.

What did your research process look like?

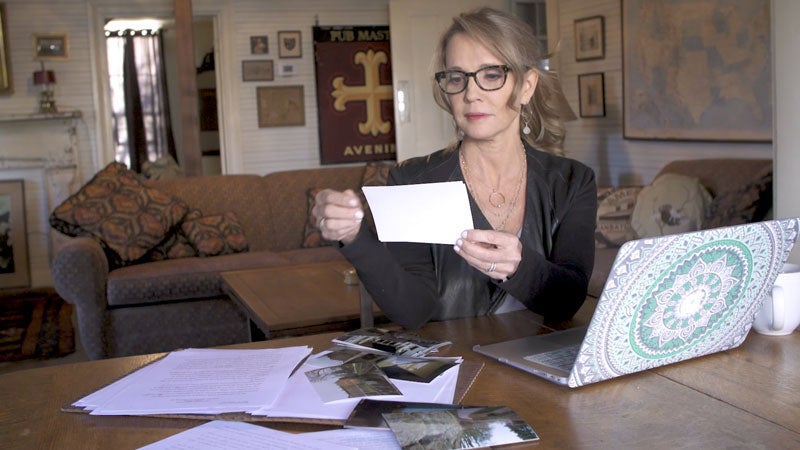

I started with what other people have written about her. Then I read everything from her point of view. I went to the Marian E. Wade Center at Wheaton College and read her unpublished letters, poems and short stories to get her voice and know how she was feeling. I could see her sitting at a typewriter struggling with her feelings. I also met with Lyle Dorsett, who is a professor in Birmingham and wrote her first biography in the ‘80s. I didn’t meet her son until the book was done, but he’s been incredibly supportive.

I also went to London to the places she talks about in her letters, and to Oxford—what I call “the places of Joy.” I went to Jack’s house and to Magdalene College where he taught, to The Eagle and Child and other pubs. I left like I was visiting a place I had dreamt about.

Patti in Oxford

You mention that a lot of things written about Joy are critical. What are your thoughts on that?

She was very judged, and at first I couldn’t figure out why sometimes people were very harsh, calling her names like brash and abrasive, where I would call her fiery and brave. When the world wants to call her names for leaving her husband or setting on a career path or being a divorced woman in Oxford, those insults show no recognition of her hurt and vulnerability. They are easy boxes to put her in. Once you call someone a name, you don’t have to know them as a person. I wanted to show a vulnerable, hurting woman with a father who was cruel and a husband who was philandering. I wanted to show why she was the way she was, and also that she wasn’t those things.

Can you talk some about your writing process?

My office had timelines, dates, lists of when their books were published, every little thing. Once I built that skeleton, dressing it was so much fun. From reading so much of Joy’s writing, she was so in my head that I knew her voice and how she would say something. Of course I can’t be 100 percent right, but I let her live through me.

What was most surprising as you learned about Joy’s life?

I’d say how wide and big her life is even though it wasn’t long. She wrote two novels and volumes of poetry, and she was a screenwriter for a year. I was so surprised by all the twists and turns of her life. She died when she was 45, and like I did, she had breast cancer. If they would have caught it, she might have lived.

What were your impressions as you read Joy’s writing?

She is incredibly articulate. She means what she says and she says what she means. Her metaphors are what make her poetry, and they ring true. She had an incredible sense of social justice, which is what she won her Yale Younger Poets Award for for poems about the Spanish Civil War called Letters to a Comrade. At times her writing can be sharp and pointed. She was a very harsh critic. The world pained her.

Do you see men reading this book?

Do you see men reading this book?

I think this story is universal. Yes, it’s told from her point of view as a woman, but my PR team came up with the greatest tagline: “You don’t know Jack until you’ve met Joy.” You get to know Jack in a new way—how upset he was when he thought he had no more stories to tell and how she relit that fire. I don’t think you know anyone fully until you know them in relationship to something else or someone else. Jack and his work stand alone, but he becomes more real when you see him in a relationship.

People don’t want to think about him struggling, but of course he struggled. And of course he had doubt. Of course he fell in love. Of course he didn’t want to ruin his image in Oxford. I put in the book that he was passed over twice for promotion because they considered him too much of a popular writer instead of an intellectual writer.

It’s not a gushy love story. It’s a story of two minds coming together over questioning and debate and trying to understand their life and make choices—all the things that make us human in a relationship.

What category would you put the book in?

I consider it a transformational journey of two people whose lives were transformed because they met on paper with words. Words build our lives, and they fell in love over discussion and debate because they were pen pals for three years. It’s a spiritual book because Joy’s transformation starts with a mystical experience that she doesn’t understand, and she calls that mystical experience God. Everything she did from that point forward is to understand that experience, which began a spiritual quest on which she met Lewis.

If someone wants to read some of Joy’s work, where should they start?

If someone wants to read some of Joy’s work, where should they start?

Pick up a book of her poetry, A Naked Tree: Love Sonnets to C.S. Lewis and Other Poems. There’s also Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman; I always want to send people to the source. If you want to read what she thought after her conversion, read Smoke on the Mountain. It’s her view of the 10 Commandments from being Jewish to atheist to Christian. There’s an amazing essay at the front of it called “On Fear.” That essay and her letters and poetry will let you see all the phases of life she went through from doubting to angry to acceptance.

An Evening with Patti Callahan

Becoming Mrs. Lewis

Monday, Oct. 1

6:30-8:30 p.m.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

Tickets, $35 each, include a signed first edition of the book and can be purchased at alabamabooksmith.com. A special private reception begins at 6 p.m.; tickets, $100 and include wine, food and preferred seating. All proceeds benefit Sawyerville Episcopal Day Camp in the Black Belt, and the event is sponsored by the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama and Alabama Booksmith. Find tickets and more information here.