Genevieve DuPré didn’t want the tennis racket her parents bought her as a child, but little brother Pat did.

“It wasn’t even a question of her even using it,” recalls Pat DuPré. “They bought three tennis rackets and (the third one) was basically for her. She didn’t use it one time so I got on the court with it right away.” So began a life on the court that continues to this day.

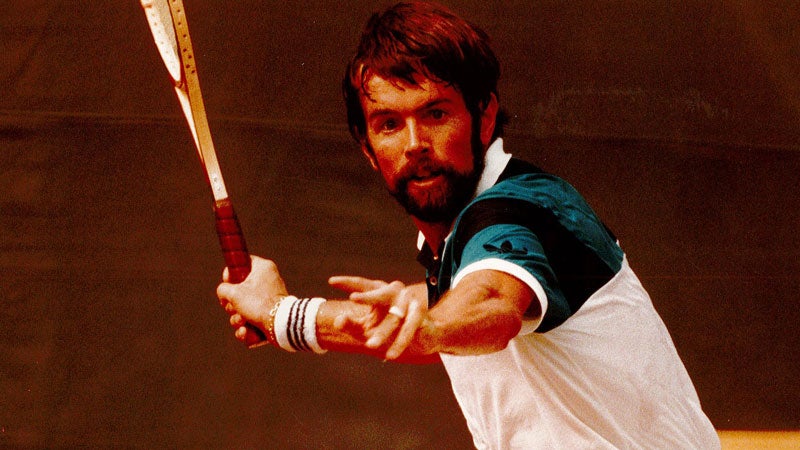

Born in Belgium and raised in Mountain Brook, Pat became one of the greatest tennis players this state has produced, a player who rose to a world No. 14 ranking while knocking off the likes of John McEnroe, Ivan Lendl, Mats Wilander and Guillermo Vilas and stepping into multiple halls of fame.

Born in Belgium and raised in Mountain Brook, Pat became one of the greatest tennis players this state has produced, a player who rose to a world No. 14 ranking while knocking off the likes of John McEnroe, Ivan Lendl, Mats Wilander and Guillermo Vilas and stepping into multiple halls of fame.

His father, Jules DuPré, was his first hitting partner. Rumor has it they played so much that young Pat would go through a pair of tennis shoes in a week. “That’s probably an urban legend but there’s no question I was going through equipment pretty quick,” says Pat, now a 63-year-old living in Savannah, Georgia. “I did play a lot. I went to school and right after school it was tennis until dinner time, and then we would repeat, and repeat and repeat.”

The two played virtually every day, even after the son got really good. Sometimes his father and younger brother Frankie would be on the one end of the court and he on the other. “My younger brother was a pretty good tennis player too,” Pat says. “My success was based upon the help I got from my dad. I got additional help from others but the foundation of everything I did came from playing with my dad.”

Jules DuPré was also Pat’s first coach. The eventual pro calls himself a patient serve-and-volleyer. He says his father was a great athlete who played ice hockey in the Olympics and in world championships.

But the father’s style as a tennis player didn’t match that of his son. “If you were to watch him play tennis and watch me play tennis, you would say: ‘How in the world did I come from that?’” Pat says with a laugh. “He was the consummate hacker. I got the (athletic) gene pool to compete at that level from him. It was a lot of coaching, but it was also hitting ball after ball after ball.”

But the father’s style as a tennis player didn’t match that of his son. “If you were to watch him play tennis and watch me play tennis, you would say: ‘How in the world did I come from that?’” Pat says with a laugh. “He was the consummate hacker. I got the (athletic) gene pool to compete at that level from him. It was a lot of coaching, but it was also hitting ball after ball after ball.”

Tennis became a family affair as his mother Lisette—“a pretty good athlete too”—also played.

“I honestly don’t know how it progressed but I got good pretty fast,” he recalls. “There was never a question that I was going to continue doing this. By the time I was in high school, I was beating every player in the state of Alabama—adult or child, it didn’t matter. I already knew at that point what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

As Pat developed as a player, father and son took a “next guy” approach to his playing schedule. “Growing up in Birmingham, I’ve got to beat this guy in Anniston,” he recalls. “Or I’ve got to beat this kid down in Pensacola or Mobile.”

John Callen, executive director and COO of USTA Southern, was one of the players on Pat’s list. “We were friends but I was a year ahead of him,” John recalls. “I would say our rivalry was first but he was certainly a friend coming up and a heck of a rival.”

“He (John) went to Ramsay High School (and) I went to Mountain Brook,” Pat recalls. “We played each other in state high school tournaments and he was always one of the tougher guys for me to beat in the metropolitan Birmingham area.

“I don’t remember at what point I started winning most of the time, or all of the time,” the eventual pro player says. “He was clearly the strongest competition for me at a younger age. He was probably the guy I had to beat to win the high school state high school tennis tournament.”

Pat was a three-time Alabama state singles champion while playing at Mountain Brook High School. He ranked second in the United States in boys 18 singles in 1971. Before long his pursuit of the “next guy” expanded beyond Alabama, to tournaments in St. Louis, Louisville, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Kalamazoo, Michigan. As his mother drove him to tournaments throughout the region and beyond, he and his father made a deal.

Pat was a three-time Alabama state singles champion while playing at Mountain Brook High School. He ranked second in the United States in boys 18 singles in 1971. Before long his pursuit of the “next guy” expanded beyond Alabama, to tournaments in St. Louis, Louisville, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Kalamazoo, Michigan. As his mother drove him to tournaments throughout the region and beyond, he and his father made a deal.

“If I made the semifinal of the tournament, my dad would drive up after work on Friday to see me play on Saturday,” he recalls of his father, an engineer who ran a pipe manufacturing company in Anniston. “He did that four years in a row, every year, because I always made it that far.”

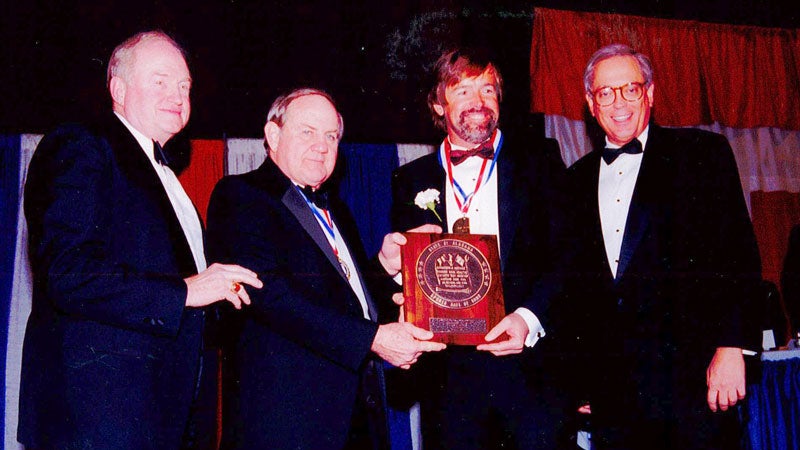

John says Pat was a player you relished—and dreaded—playing. “You certainly get up for a match for somebody like Pat,” says John, who like Pat is in the Alabama Tennis Hall of Fame and the Southern Tennis Hall of Fame. “But you also dread the fact that he’s on the other side of the net. You know he’s going to give it his best and that’s going to be tough to beat.”

Pat was the first tennis player enshrined in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, and is in the International Collegiate Tennis Hall of Fame. “He was always just tough as nails and was getting better every year,” John says. “Certainly, when he went to Stanford everything just exploded for him.”

Pat was the first tennis player enshrined in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, and is in the International Collegiate Tennis Hall of Fame. “He was always just tough as nails and was getting better every year,” John says. “Certainly, when he went to Stanford everything just exploded for him.”

Pat was an All-American for four years in college. In 1973 and 1974, he helped lead Stanford to a pair of National Collegiate Athletics Association national championships. When he moved on from the Cardinal, Pat took his gritty play to the pros, where he notched one singles title on the ATP Tour at the 1982 Hong Kong Open and snared four doubles crowns.

The former Mountain Brook Spartan was a semifinalist at Wimbledon in 1979 and a quarterfinalist at the U.S. Open. Along the way, he notched wins against nearly every opponent.

Jimmy Connors and Bjorn Borg were the exceptions. “Borg used to beat the crap out of me,” Pat says. “Whatever I tried just didn’t do any good. Connors, on the other hand, we had a lot of very close matches. Unfortunately, I never won one, but there were a lot of real close ones. I didn’t cross the finish line, but I always felt like there was a chance there.”

Pat still enjoys playing tennis and gleans nearly as much pleasure out of teaching and coaching the game. He has developed a tennis business in Savannah with about 200 clients, teaching them on private courts and in public parks.

“I’m one of the lucky ones who gets to say he doesn’t have to work a day in his life, which is a lot of fun,” he says. “I do enjoy coaching, I really do. Whether it’s a 5-year-old kid hitting the ball for the first time or teaching a group of elderly ladies how to win at doubles or teaching a kid to a national junior championship. They’re all very satisfying.

“It’s not work to me at all. It’s a heck of a lot of fun.”