A bell rings, and with that it’s time.

“Divinia, you are up. Declarations please,” Mountain Brook Junior High teacher Paul Hnizdil says. “If you are solving crises, please help us with what crises you are dealing with so we can all look.”

With that, one of his ninth-grade advanced world history students stands up, only in this moment her title is not student. “I am Prime Minister Bryant of Divinia,” she states. “We are declaring war against the mercenaries of the island.”

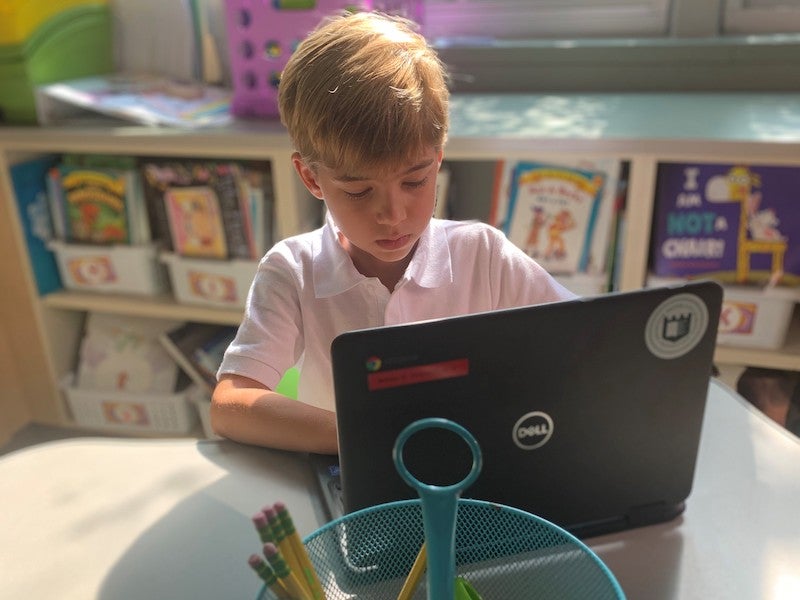

War? In history class? Yes, in fact. It’s all a part of a geopolitical simulation called the World Peace Game that is underway. Divinia has purchased an island from neighboring country Kapistan, but they are not allowed to claim complete ownership of the island until the mercenaries are gone. Hence, the war.

“Are you prepared to write letters to the letters of the families of the fallen?” Hnizdil asks Prime Minister Bryant. They are.

“Are you going to kill or capture?” Hnizdil asks. “At some point you have to decide. It costs $1 million a day for POWs. Do the battle first and then decide.”

With that the weather god, another student’s role, tosses a coin. It lands on tails, so the first battle was lost. Next it lands on heads, so the second battle was won. “This is it, you have a 50/50 chance here,” the weather god says. Again it’s tails, and the battle was lost and the war too.

The Divinia officials select icons representing 12,000 of their own mercenaries and a tank battalion wiped out by island’s mercenaries off a four-story plexi-glass playing board in the center of the library where the game is taking place.

Because they are hired soldiers, not volunteer soldiers, do the national leaders write letters to their families too? “Mercenaries are still people,” the weather god says. So yes, they need letters, due two game days from now.

Next up it’s time to spin the wheel. For a moment this Risk-like game shifts to look more like Wheel of Fortune. The verdict? Heat wave. But it could have been a blizzard, sand storm, hurricane, tsunami or simply cloud cover.

And then it’s time to draw a card. “Drones accidentally fire on the village of a tribal chieftain,” it reads. “No one is hurt, but the entire village is destroyed.” The weather god grabs a drone off the board and moves it over to Divinia’s space.

With that, Divinia’s turn is over. Further around the circle sit officials from three other countries plus those from three agencies: World Court, World Bank and an Arms Dealer. And once each of those entities has taken a turn, one game day ends.

This is part of the third time Hnizdil—his students often call him “Niz”—and MBJH librarian Tami Genry have led students through the World Peace Game simulations since going through a weeklong training for it funded by the Mountain Brook City Schools Foundation in spring of 2019, and following this session they are planning to scale it to other classes in the school too. Each game starts with four days of instruction and preparations before the 11 class periods it takes to solve the 23 crises the students start with to complete the entire game.

Not long after Divinia’s war ends another crisis is solved when an investigation is launched to

decide if an island is a burial ground. Two coin tosses later, the investigation is complete. There are no bones, and with that Crisis No. 8 can be checked off their list.

The next order of business today is a little more controversial. A treasure of undersea artifacts has been found, and all ownership is going to the country of Snowlandia, who then is giving 15 hydrogen cell plants to each other country.

“You realize all the species will die?” Hnizdil asks the country’s officials.

“Yes, but it’s for the greater good because if not the whole world is going to die,” their prime minister responds.

“And your undersecretary for environmental affairs agrees with that?” Hnizdil retorts. The response is yes, and he turns to another country.

“Divinia, you are our ecologically minded nation. Did you sign that agreement?” Hnizdil asks.

Everyone has signed it.

“Legal counsel, do you agree to that?” he asks turning to another spot in the circle. They do.

The last decision is with the weather god.

“I’m just saying a lot of terrible acts have been for the greater good,” the weather god reasons.

“Do you accept?” Hnizdil asks.

“Regretfully, yes,” the weather god says. “I’m between a rock and a hard place.”

With that Crises No. 19 is solved, and all the world officials applaud before another round of negotiations begins.

“The conversations are incredible,” Genry notes as the students work on their own. “They always start off playing for themselves and their country, but (eventually) they realize they can’t achieve world peace that way and they eventually start helping each other solve crises. ‘Oh no your prime minister got overthrown, let me help you,’ they’ll say. The game is designed so that the biggest outcome in every game is understanding.” And that understanding sinks in further as the students go home and work on reflections each night after a game day.

Following training last year, Genry and Hnizdil were tasked with developing their own playing board. Each level of the plexi-glass represents a different element: sea, land, sky and space. Each country has designated air space above and sea below, and they share international air space and waters.

On the top layer, you’ll find space stations and one black hole a crisis has to solve. Further down are missile launchers and boats, medical facilities and university towns—some icons made by the school’s robotics department on a 3D printer and others purchased online. “It involves a lot of details, and you never know which direction the game is going to go,” Genry notes, explaining that what you won’t see is an oil spill on the board. That crisis has already been solved.

Speaking of crises, before long the game bell rings again, and declarations begin again before the 48-minute class period ends.

It’s time to read a letter to fallen soldiers. “To the families of the fallen soldiers,” the weather god reads. “The nation of Kapistan has to inform you with great regret that you have lost a loved one in battle. Know your family’s loss was not in vain as the battle was won. Thank you, Secretary of States of Kapistan.”

Even in these short 48 minutes, it’s obvious the aims of the game’s creator John Hunter, who trained Genry and Hnizdil, are at work. There’s chaos, there are pressures and a sense of urgency, there’s competition, and yet there’s collaboration, there’s empathy and compassion and perspective is gained. In the end, problems are solved, and world peace will arrive. And it won’t be too many years before these ninth-graders are applying those same principles not to Divinia and Kapistan but to the world around them, with peace in mind.

A Foundation for the Game

The World Peace Game came to Mountain Brook Junior High thanks to funding for training from the Mountain Brook City Schools Foundation. The foundation provides grants for professional development, technology and library enhancements in Mountain Brook City Schools. Learn more or give at mbgives.org.